- Author

- Books

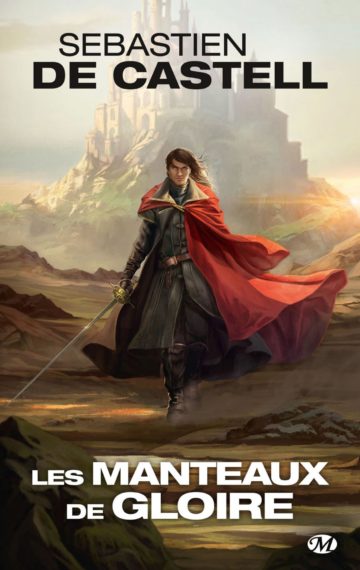

- The GreatcoatsThe acclaimed swashbuckling fantasy quartet

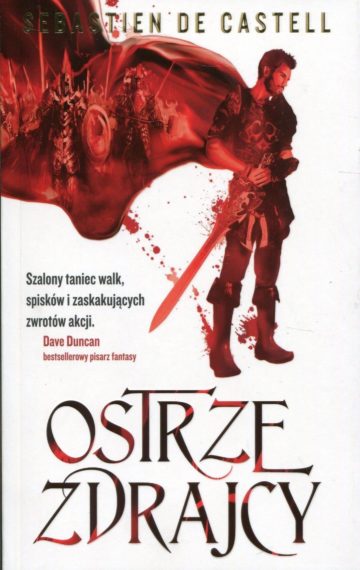

- Traitor’s BladeCan a disgraced swordsman save a young girl caught in the web of a royal conspiracy?

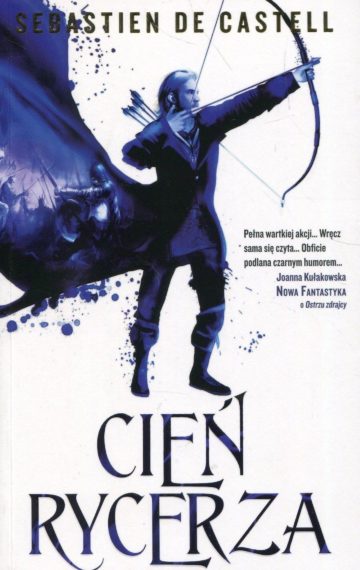

- Knight’s ShadowWill Falcio unite a warring kingdom before the poison in his veins takes his life?

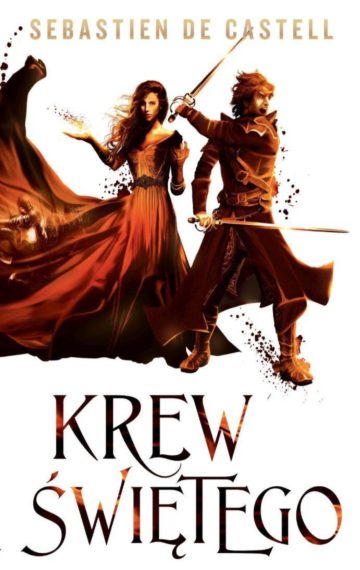

- Saint’s BloodSomeone has found a way to murder the saints, and only Falcio can stop them.

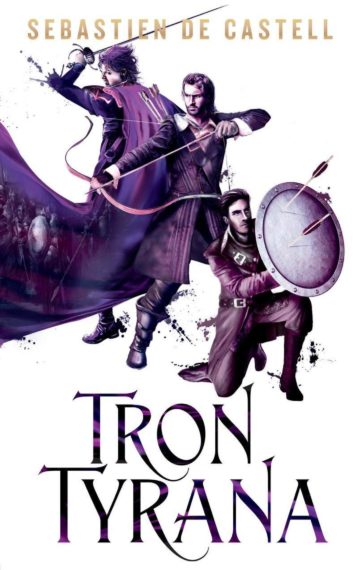

- Tyrant’s ThroneFalcio has one chance to restore the rule of law in Tristia, but will can pay the price?

- Tales of the Greatcoats Vol. 1The first collection of swashbuckling short stories featuring the Greatcoats!

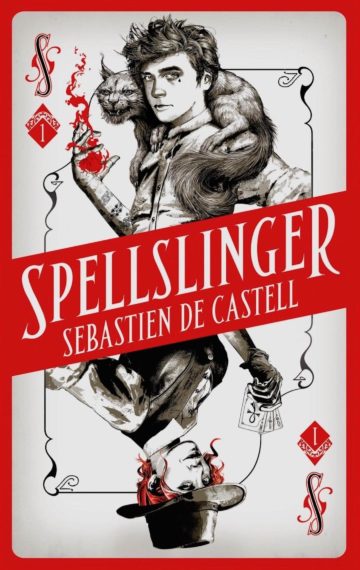

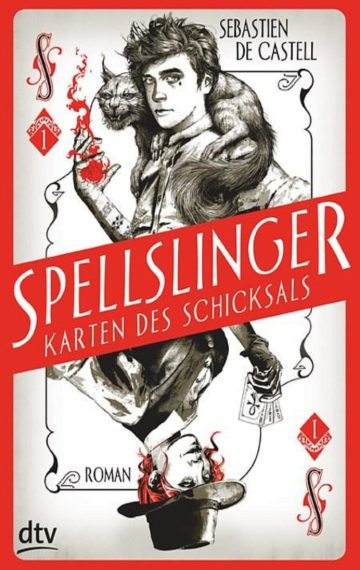

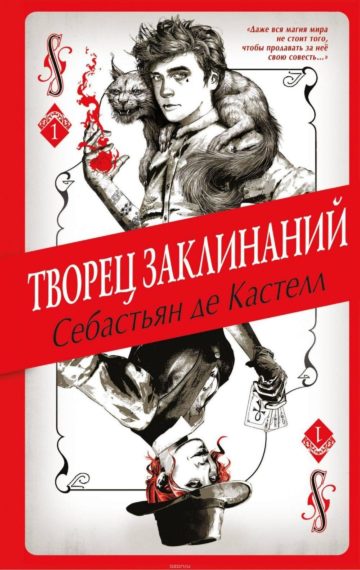

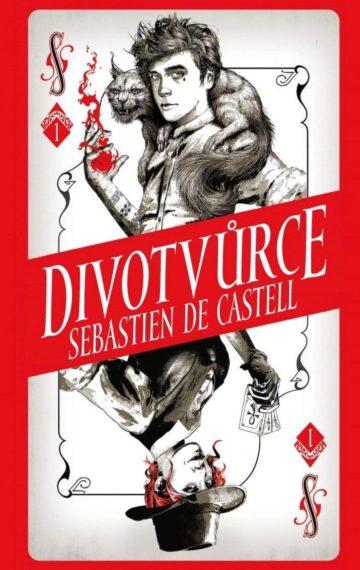

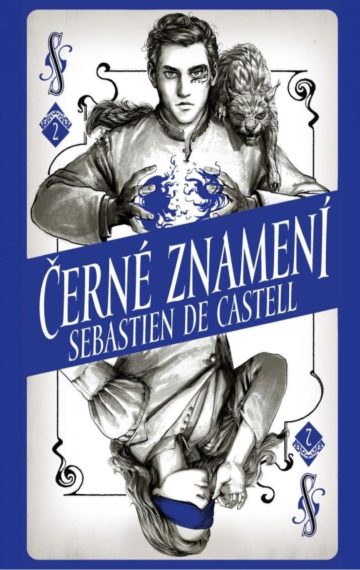

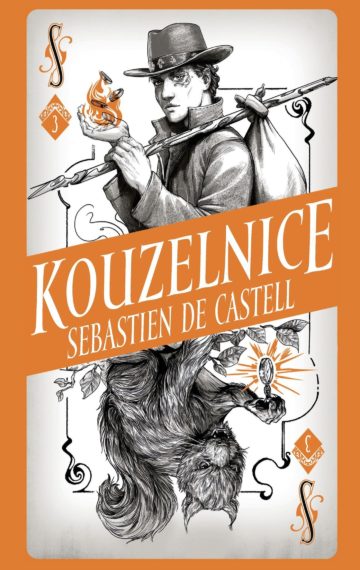

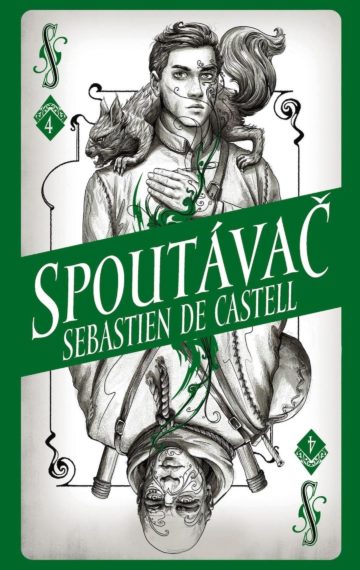

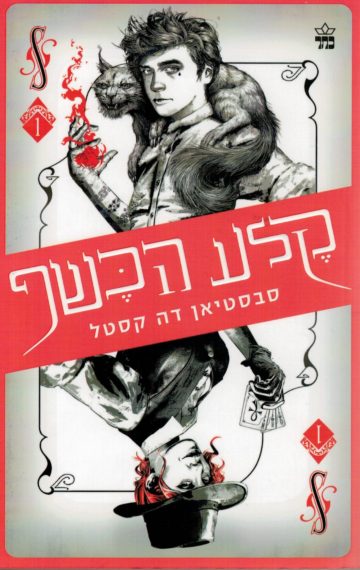

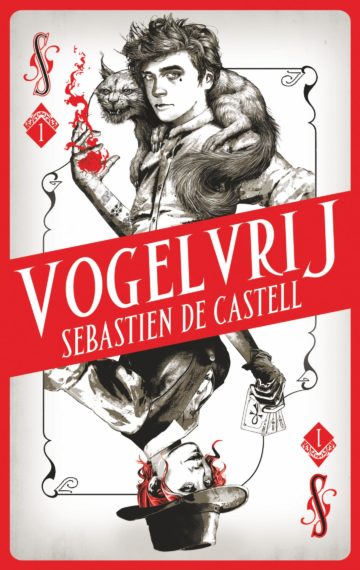

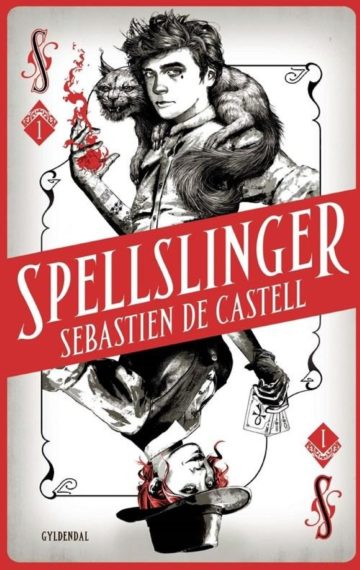

- SpellslingerMagic, tricks, traps, and a talking squirrel cat.

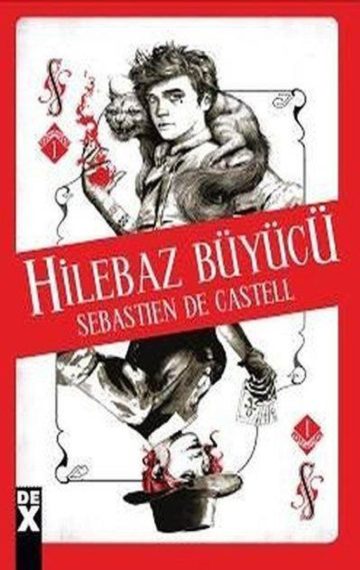

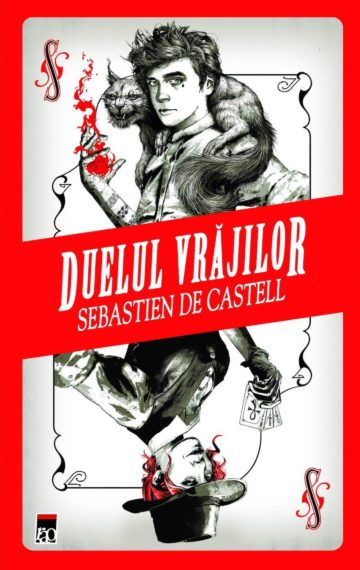

- SpellslingerKellen would give anything to pass his mage’s trials, but what if magic is a con game?

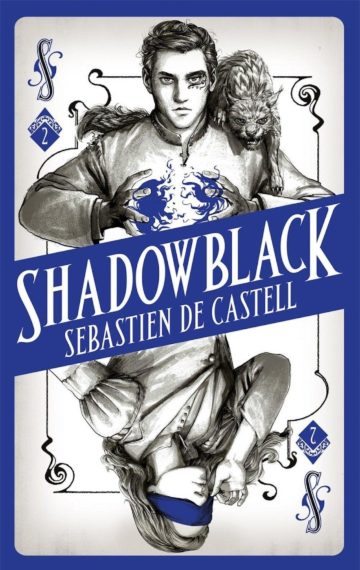

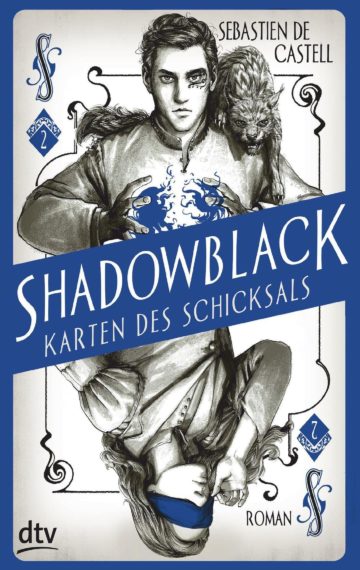

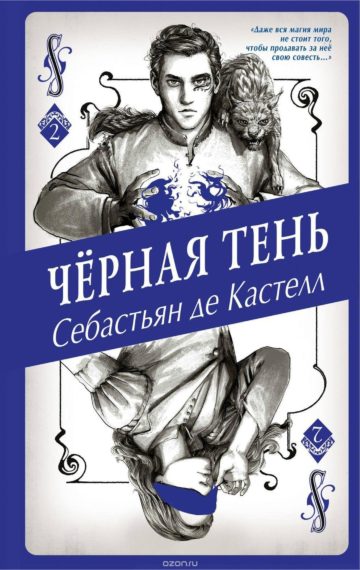

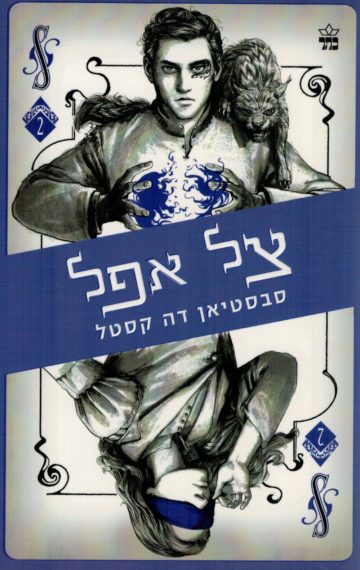

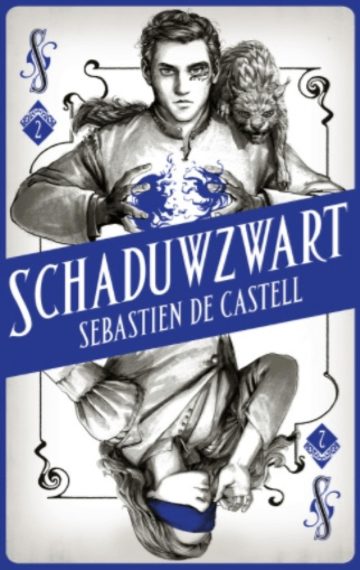

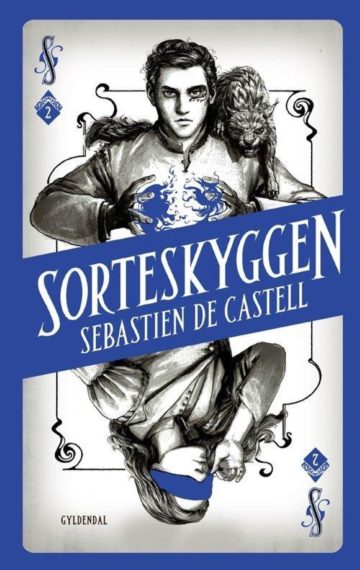

- ShadowblackOutlaw life isn’t what Kellen expects when he uncovers a mystical plague.

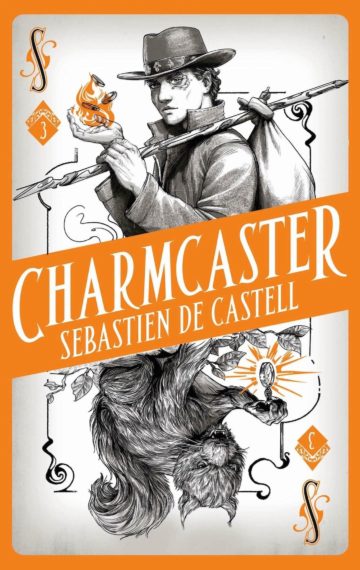

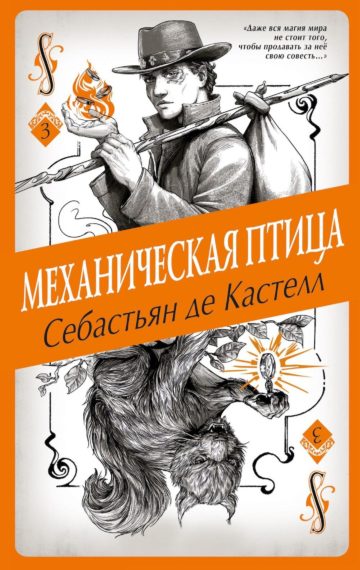

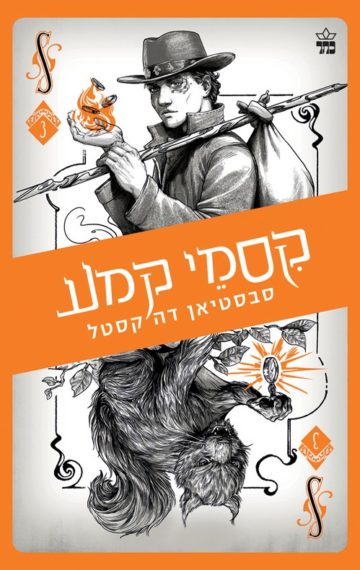

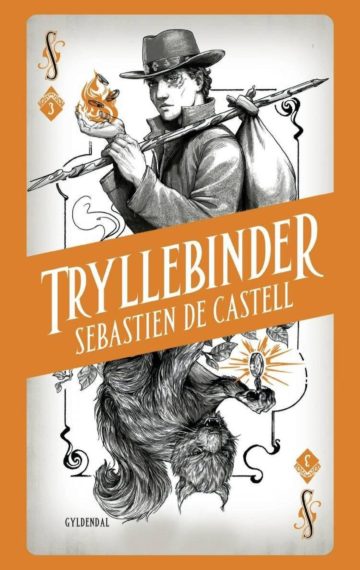

- CharmcasterKellen’s travels bring him to a land where destiny has a dark side.

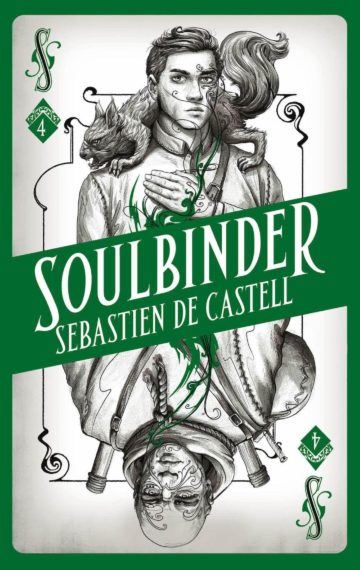

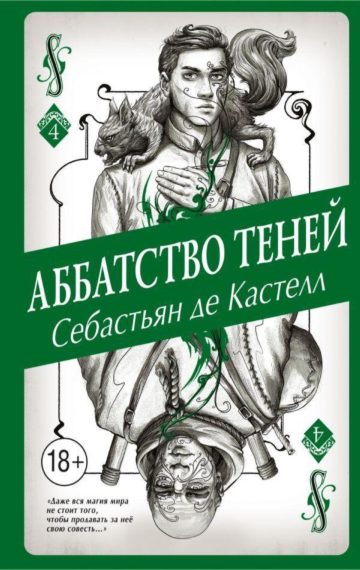

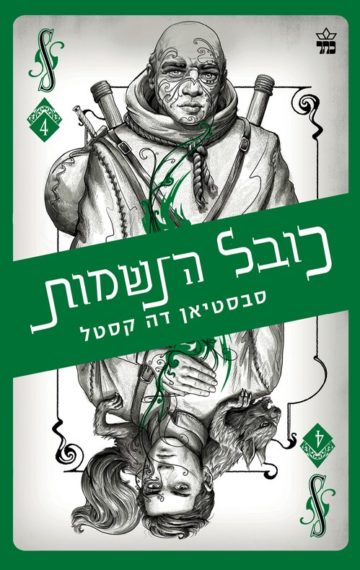

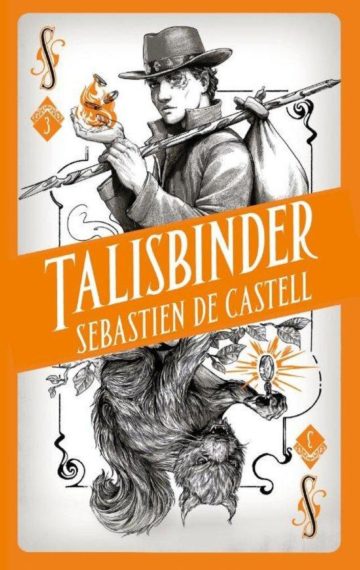

- SoulbinderKellen tries to rid himself of the shadowblack and discovers fate can be fatal . . .

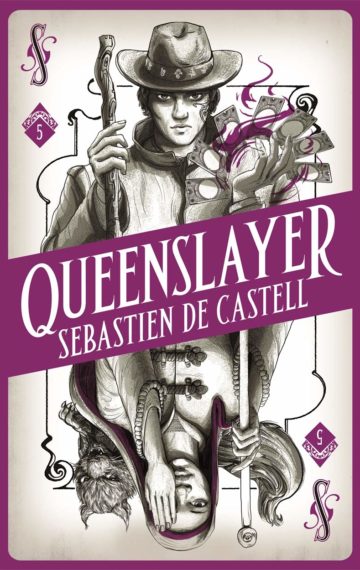

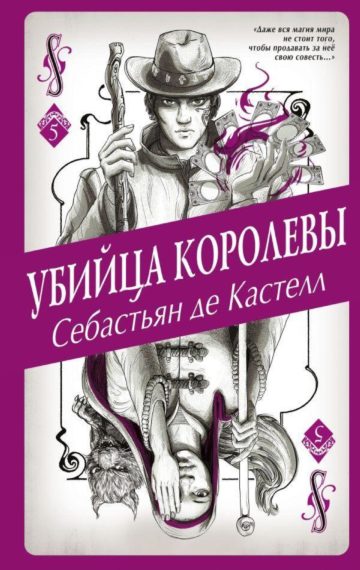

- QueenslayerWeary of outlaw life, Kellen unwittingly becomes a pawn in a game of empires.

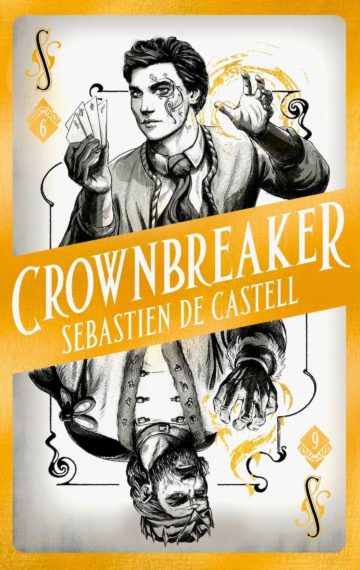

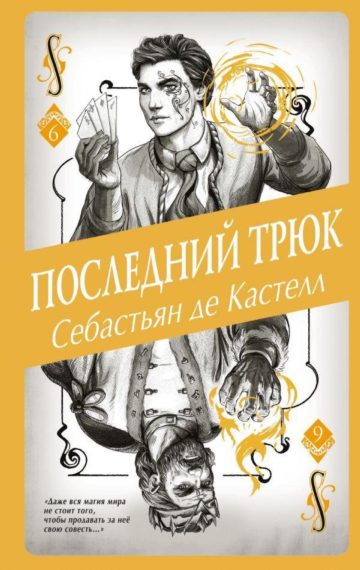

- CrownbreakerKellen’s vow to protect a young queen may demand a terrible price.

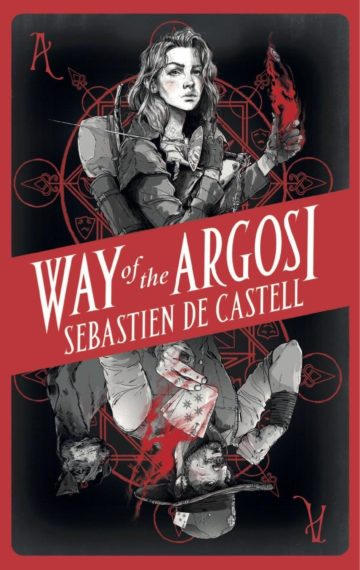

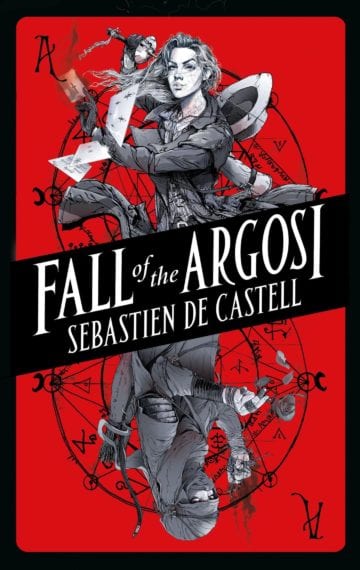

- The ArgosiLearn the secrets of the Argosi and the origins of the legendary Ferious Parfax!

- Court Of ShadowsA new darkness threatens and new heroes rise to face it.

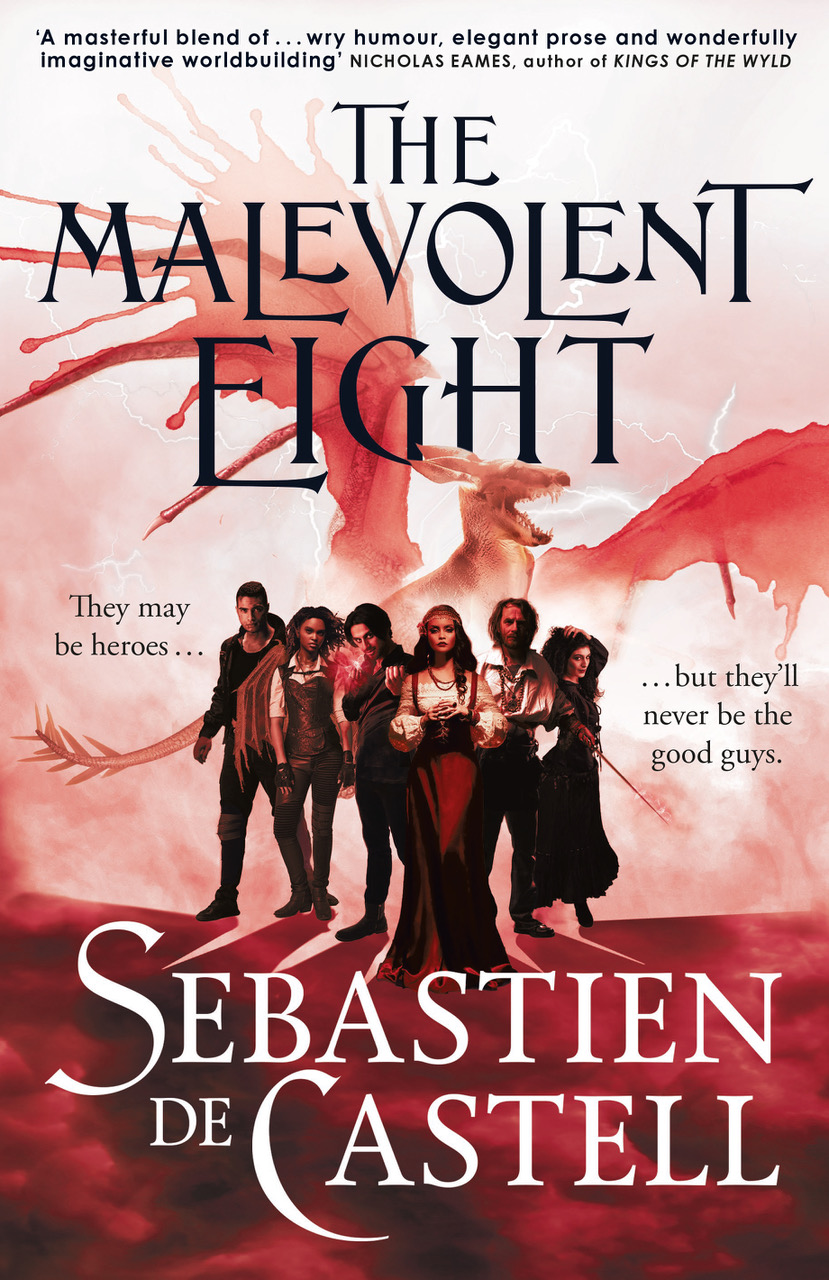

- Malevolent SevenTime to recruit some very bad people

- Author ExclusivesShort fiction and audiobooks available exclusively from the author.

- Signed EditionsGet signed and personalized books sent right to your door.

- The GreatcoatsThe acclaimed swashbuckling fantasy quartet

- Blog

- TravelVisiting new places is one of my favourite activities.

- AdventureSometimes we all need a little adventure in our lives.

- Book NewsLatest news on upcoming releases

- Author LifeWeird tales from the land of book publishing.

- Story JournalsNotes along the way as I write each book.

- ReadingOccasionally I find time to read books.

- ArticlesWriting advice and fantastical musings.

- Secrets

Les vieux maîtres de sort aiment raconter que la magie a un goût. Les sorts de braise ressemblent à une épice qui vous brûle le bout de la langue. La magie du souf e est subtile, presque rafraîchissante, un peu comme si vous teniez une feuille de menthe entre vos lèvres. Le sable, la soie, le sang, le fer… cha- cune de ces magies a son parfum. Un véritable adepte, autre- ment dit un mage capable de jeter un sort même à l’extérieur d’une oasis, les connaît tous.

Les vieux maîtres de sort aiment raconter que la magie a un goût. Les sorts de braise ressemblent à une épice qui vous brûle le bout de la langue. La magie du souf e est subtile, presque rafraîchissante, un peu comme si vous teniez une feuille de menthe entre vos lèvres. Le sable, la soie, le sang, le fer… cha- cune de ces magies a son parfum. Un véritable adepte, autre- ment dit un mage capable de jeter un sort même à l’extérieur d’une oasis, les connaît tous. 'I totally saw this coming,’ Reichis growled, leaping onto my shoulder as lightning scorched the sand barely ten feet from us. The squirrel cat’s claws pierced my sweat-soaked shirt and dug into my skin.

'I totally saw this coming,’ Reichis growled, leaping onto my shoulder as lightning scorched the sand barely ten feet from us. The squirrel cat’s claws pierced my sweat-soaked shirt and dug into my skin. The way of the Argosi is the way of water. Water never seeks to block another’s path, nor does it permit impediments to its own. It moves freely, slipping past those who would capture it, taking nothing that belongs to others. To forget this is to stray from the path, for despite the rumours one sometimes hears, an Argosi never, ever steals.

The way of the Argosi is the way of water. Water never seeks to block another’s path, nor does it permit impediments to its own. It moves freely, slipping past those who would capture it, taking nothing that belongs to others. To forget this is to stray from the path, for despite the rumours one sometimes hears, an Argosi never, ever steals.